Strategic balance: Ali Larijani reassesses the Iran–Lebanon alliance in face of US pressure

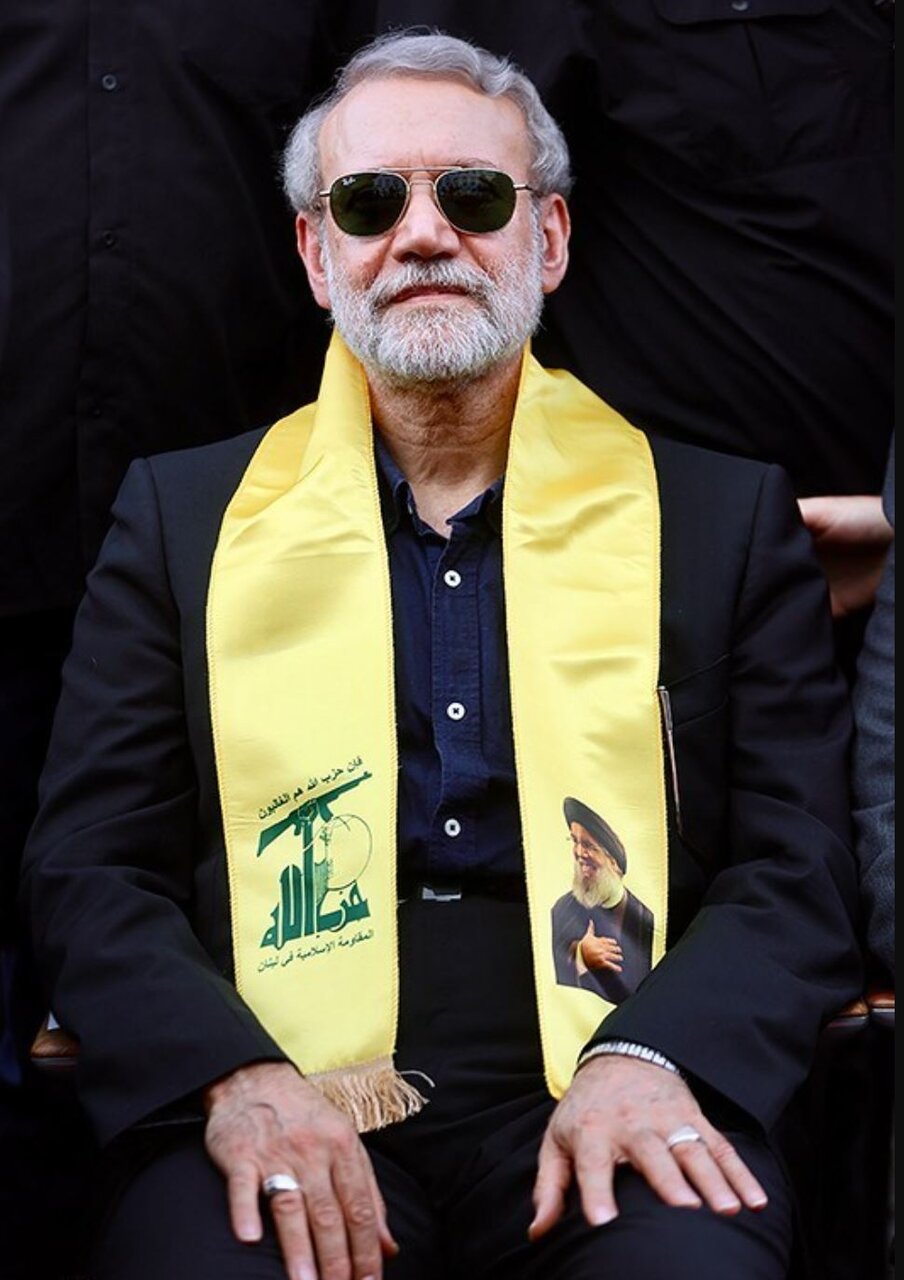

MADRID – Ali Larijani’s recent visit to Beirut, in his capacity as secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, marks a significant moment in the Islamic Republic’s diplomacy and its relations with a country that remains central to the political chessboard of West Asia.

Far from being a mere protocol visit, Larijani’s trip carries deep symbolic and political weight at a time when the region is beset by instability, mounting international pressure, and the ever-present Israeli threat.

Larijani arrived in the Lebanese capital accompanied by senior officials and members of parliament, coinciding with the commemoration of figures emblematic to Hezbullah, such as Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah and Sayyed Hashem Safieddine. Yet the broader context of this journey, as he made clear in his public statements, was the renewal of strategic ties between Tehran and Beirut, along with a reaffirmation of a regional axis committed to independence, sovereignty, and cooperation in the face of destabilization efforts and external hegemonic ambitions.

In his first remarks, cited by Lebanese media and Iranian agencies, Larijani stressed a central aspiration of Iran’s foreign policy: “Our hope is that regional governments be independent and strong; today, faced with Israel’s conspiracies, countries must come closer together and cooperate in good faith.” This message, beyond diplomatic rhetoric, evokes a principle that has guided the Islamic Republic since its inception: political autonomy and rejection of foreign tutelage or interference—whether by the West, external actors, or rival regional powers.

Iran–Lebanon relations have shaped the political agenda of both countries since the difficult 1980s. Ties have deepened not only through support for Hezbollah as a Resistance movement, but also via multifaceted cooperation encompassing technical advice, humanitarian aid, and economic exchanges. In a climate where pressure on the Resistance Axis constantly resurfaces, Larijani’s visit may be read as an act of presence that sends an unmistakable signal to both allies and adversaries: Iran is not retreating but rather reinforcing its commitment to Lebanese sovereignty and stability.

During his trip, Larijani met with key Lebanese state figures, including parliamentary speaker Nabih Berri and prime minister Nawaf Salam, as well as Hezbollah leaders and representatives of other political forces. Beyond protocol, these meetings allowed him to outline a vision of regional security centred on dialogue and cooperation—two pillars of Iran’s current strategic thinking.

“Lebanon is a friendly country,” Larijani told reporters. “We consult on all matters, especially in moments of rapid change.” The timing of these words—during ceremonies commemorating great figures of the Lebanese Resistance—was deliberate. By attending a memorial for Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, whose leadership against Israeli incursions and occupations defined an era, Larijani underscored a dual message: honoring martyrdom while invoking shared memory as a binding element of transnational solidarity.

The visit took place amid Lebanon’s multidimensional crisis—political, economic, and security-related—that keeps it under intense international scrutiny. True to the Islamic Republic’s proactive stance, Larijani insisted that strengthening Arab state institutions is the best response to externally encouraged fragmentation.

Addressing immediate threats, he did not shy away from Israel: “Today, the region requires joint mechanisms of cooperation to overcome our common threat.” In this regard, he recalled the enduring legacy of leaders like Hassan Nasrallah, who foresaw the Israeli danger and helped forge the first generation of fighters who shifted the balance of power in southern Lebanon.

Resistance as a cornerstone of security policy

Larijani’s presence at Hezbollah’s memorial also reaffirmed the centrality of resistance as a pillar of the region’s security architecture. While Iran has never denied its political and moral support for Hizbullah, this time the emphasis fell on the movement’s nationalist dimension. “Lebanon may be small, but it is strong against Israel. Ultimately, this is thanks to the unyielding will of its youth,” Larijani stated.

The tribute to martyrs and recognition of the resistance is not mere optics: it aims to consolidate internal unity and construct an alternative narrative to hegemonic accounts that reduce Hezbollah to a mere Iranian proxy. In Larijani’s discourse, the party–militia appears above all as the legitimate shield of the Lebanese people—capable of maintaining an autonomous national line and cooperating with other forces for the sake of stability.

In his press briefings, Larijani referred to recent statements by Sheikh Naim Qassem, Hezbullah’s secretary-general, regarding the possibility of normalizing relations with Saudi Arabia. “I welcome Sheikh Qassem’s initiative,” Larijani said, “and value his call for opening a new chapter in intra-Islamic dialogue.”

He stressed that Saudi Arabia, despite its differences with Iran, remains a brotherly state in the Muslim world. “History shows us that in critical situations, Muslim nations must set aside disputes and prioritize cooperation against common threats. The logic of internal enmities only weakens us all, while the real goal must be strengthening the Islamic front against the Israeli threat.”

Acknowledging recent Saudi–Lebanese contacts, he added: “Every step, every mediation that brings peace of mind to the Lebanese people deserves support.” In this way, Iranian policy reaffirms its preference for active, pragmatic diplomacy: open to political agreements and coordination rather than rigid dogmatism.

Reconstruction and humanitarian commitment

Recent Israeli military campaigns in Lebanon have destroyed thousands of homes. Asked about Iran’s role in reconstruction, Larijani tied material support to the principles of Iran’s foreign policy. “Lebanon’s destiny must be decided by the Lebanese themselves,” he said, “but I can assure you that we are working to make the rebuilding of homes destroyed by Israeli occupation a priority of international cooperation.”

His emphasis on respecting Lebanese sovereignty also sought to distance Tehran from narratives accusing it of interference: “Lebanon does not need guardianship. We will always support its processes, but it is for the Lebanese to chart their own course,” he declared.

The visit also provided an opportunity to respond to recent U.S. allegations that Iran supplies Hezbollah with resources and weaponry. Larijani was blunt: “I have read these accusations, but they are baseless. Hezbollah has grown so strong that it no longer depends on external shipments. They have sufficient internal capabilities to defend their people and maintain peace.”

He likewise dismissed U.S. interference in Lebanon’s internal politics and in decisions concerning Hizbullah’s role relative to the Lebanese army: “The United States places itself as Lebanon’s tutor. We view this paternalistic, foreign approach as a source of problems, not solutions.”

Asked whether Iran is pushing for convergence between Hezbollah and Saudi Arabia, Larijani stressed that Tehran’s policy is non-impositional: “We do not dictate behavior. We trust the judgment of leaders like Sheikh Qassem and their commitment to the common good.”

This reflects a more sophisticated, pragmatic political calculation: that diplomacy achieves more than coercion, and that in fragile regions like West Asia, national unity is an undervalued but essential asset. Larijani highlighted Hezbollah and its Lebanese allies’ ability to prioritize coexistence and open channels of understanding over sectarianism as proof of political maturity.

The overall balance of Larijani’s visit to Lebanon underscores the breadth of Iran’s regional policy. Far from stereotypes portraying Tehran as isolated or bound solely to military logic, Iranian diplomacy here appears as a mediator, promoter of cooperation, and advocate of regional pluralism.

In this framework, resistance emerges not only as defensive action but as the driving force of a new regionalism prioritizing independence, dialogue among equals, and peaceful conflict resolution. Challenges and risks are not denied or concealed. On the contrary, Larijani emphasized the need to prepare for all possible scenarios while keeping broad cooperation as the central strategic axis.

“We are ready for any contingency,” he declared, “but we trust that reason will prevail. Recent history shows us that dividing lines only serve our adversaries.” Thus, rationality and prudence become political virtues that guide Iran and its allies’ strategic horizon.

Ali Larijani’s visit to Beirut was not only a commemoration of martyrs nor just another item in the National Security Council’s agenda. It was a visible expression of a paradigm that combines firm support, respect for sovereignty, and a willingness to foster regional cooperation.

In times of multiple threats and external pressures, Iran’s foreign policy—as reaffirmed by Larijani—remains aware of its limits and its possibilities. It does not shy away from challenges, but neither does it seek confrontation for its own sake; instead, it favors pragmatic understanding, institutional strengthening, and the building of alliances that allow each nation to decide its own destiny.

Today, as before, Iran’s position is clear: to strive for an inclusive regional order in which all actors—large or small—have the space to define their priorities, build consensus, and reaffirm their dignity against threats. Through his visit to Lebanon, Larijani has underscored the Islamic Republic’s strategic maturity, persisting in its vision of a strong, autonomous region capable of raising its own voice on the international stage.

Leave a Comment